Style

Getting all the notes of a piece under our fingers is only the first step on the way to performing. It’s what happens after this that engages the listener and makes the performance memorable. Of course, we naturally want to be different and make our playing stand out from the crowd, but it’s no good if we go a little overboard and play in the wrong style. Style is very important, and can be quite subjective. It’s something that we can always look into at a greater depth, and just one reason why musicians are always students.

Style is often dictated by the period in which the music was written. You wouldn’t expect a character in ‘Downton Abbey’ to come into a scene wearing a pair of skinny jeans, would you? Similarly, you wouldn’t want to play a piece in such a way that the listener is no longer able to understand how it could have been written in a certain period. The tone we use has a huge bearing on style. Recently, I played the beginning of the Prelude from Bach’s Partita in B flat major (BWV 825) to one of my teachers, and his first comment was that I needed to alter my tone. The sound I was producing would have been far more suited to the work of a romantic composer such as Brahms, so I needed to lighten my touch in order to make my style more appropriate for the work. The same principle can be applied to flexibility; a performer may choose to pull the tempo around in a Chopin Nocturne to a degree that would be out of character in one of Domenico Scarlatti’s sonatas.

A good way to implement style is to think about the instrument for which the music was written. Yes, you’re probably going to be thinking “erm… piano”, but remember that our instrument has come a very long way from the first pianos of Cristofori in the 1700s. Of course, the music of Bach and Scarlatti would have been written for harpsichord, an entirely different instrument indeed! This does sometimes throw up disagreements over certain aspects of playing, such as the use of sustain pedal, but as long as you think generally about the instrument, then you will be far better off than if you’d disregarded the matter!

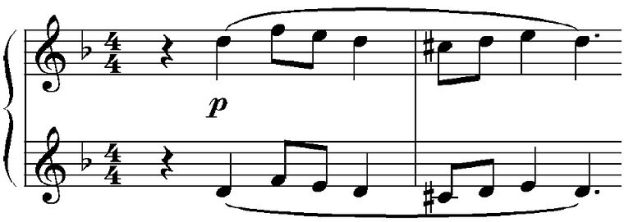

However, to play a piece stylistically doesn’t mean that you are to play in a certain way when it comes to interpretation. This is what brings originality to your playing, and makes the music as current now as it was when it was written. To demonstrate my point, below are two famous recordings of Bach’s Goldberg Variations (BMV 998), both recorded by Glenn Gould. The first was recorded in 1955, the second in 1981: both are examples of style fitting to Bach’s writing, but both recordings differ dramatically when it comes to Gould’s interpretation. You only need to listen to the opening few bars of the Aria to see my point:

Lewis Kesterton is a pianist currently studying at Birmingham Conservatoire. Read his blog here

Schubert. This entry on the letter S would not be complete, for me at least, without a mention of Franz Peter Schubert, a composer whose music I have loved and lived with all my life: as a young child hearing my father play Der Hirt Auf Dem Felsem (‘The Shepherd on the Rock’) on the clarinet, my own LP of the ‘Unfinished’ Symphony, my first encounters with the Impromptus and Moments Musicaux for piano in my mid-teens, as a precocious student who could play the notes, but who understood little of where this music came from or its emotional depth. Returning to the piano in my late 30s after an absence of some 20 years, it was Schubert’s music to which I turned first, revisiting the Impromptus initially, and then the late piano sonatas, with the benefit of musical maturity (the result of a lifetime of listening and concert-going rather than playing at that time) and life experience. As an argumentative teenager, often to be seen at weekends on CND marches, the old radical Beethoven had been my hero, a composer who wore his heart on his sleeve and whose life-affirming music declaims his existence, at once full-bodied and triumphal, but also other-worldly and philosophical especially in his late works. Schubert speaks more quietly: his soundworld is introspective, and intimate. He takes us into his confidence, and he is often at his most tragic when writing in the major key. His music packs a vast emotional punch – the range of emotions expressed within a piano miniature, such as the Impromptu in f minor D935/1, are startling, their unexpectedness underlined by his daring use of harmony and his expansiveness (which Schumann described as his “heavenly length”), underpinned by an innate sense of musical geometry and architecture. As a consequence, there are many interpretative possibilities in his music.

If Beethoven is notable for his musical structures and energy, Schubert is the spinner of beautiful melodies, music which speaks of his life in Vienna, of socialising and music making with friends, country rambles and joie de vivre (think of the joyful holiday moods of the ‘Trout’ Quintet), but always shot through with darkness and heartbreak. He had plenty of intuitions of mortality during his brief life: he contracted syphilis in 1822/23, at that time an incurable and shameful disease, and lived in a city on a continent wracked by revolution and war. These were turbulent times, both personally and politically, and his music reflects this in its emotional voltes faces – all those layers of feeling and chains of emotions – perhaps most strikingly expressed in the slow movement of the Sonata in A, D959 or in the Fantasy in F minor, D940.

Frances Wilson – pianist, writer, teacher and author of The Cross-Eyed Pianist blog.

Up, up in the highest echelons of the pianistic pantheon sits Sergei Rachmaninov….

Up, up in the highest echelons of the pianistic pantheon sits Sergei Rachmaninov….

Why pick ‘

Why pick ‘