Who or what inspired you to pursue a career in music?

There was always music being heard at home because both my parents are music lovers but actually playing the piano was introduced relatively late to me. I had many friends my age (8 at the time) who were playing an instrument and so my parents simply thought, why not?

It wasn’t until much later that I realised just what it might mean to be a concert pianist which was when I went to hear the Tchaikovsky first piano concerto at the Royal Festival Hall. The concerto captures your attention from start to finish and you can imagine how impressive it was to a child aged eleven. Of course my reaction then and what thoughts whirled in my head would not be how I hear the concerto now, but I learnt at that moment about the communication of music.

Who or what have been the most important influences on your musical life and career?

My many professors, of course, have all had an impact to my music making. One of my first professors was Christopher Elton. I was at the Purcell School and searching for a new teacher. I was introduced to Christopher and he accepted me in his class but I was this incredibly shy child who didn’t talk much to adults but was determined to make efforts through playing. Christopher was incredibly patient with me, and has, in in a way, been a musical father to me, as he has seen through all my career phases. Many, many years later, we still keep in touch and a friendship has developed since, which is always one of the nicer aspects of a musical relationship.

Then there is Maria Curcio-Diamond, who transmitted so many pearls of wisdom but I was too young to fully appreciate when I studied with her and now refer back to constantly today.

Lev Naumov was just a brilliant mind and musician and I was immensely fortunate to have had the opportunity to participate regularly in his classes.

John Lill has also been influential but I would say that however, it was the years I spent alongside Ruggiero Ricci that has had the most impact with my approach to music making today. He was heralded as a prodigy as a youth, a virtuoso as an adult violinist (a term he disliked) and the first violinist to have recorded all the Paganini Caprices. He was so modest and lived through so many experiences. I would often accompany his students in masterclasses and I learnt so much from watching him teach and from when we played together. There was something so natural and straightforward in his music making. It’s something I have tried to transmit in my own performances. It was also these years spent with Ricci that opened many doors for me, notably by meeting other musicians, some very well known, others less, as well as non-musicians but music lovers who have all had an influence into my approach to performing and life today on and off the concert circuit.

What have been the greatest challenges of your career so far?

Juggling between raising two small children and keeping up with the rhythm of giving concerts have been challenging but extremely rewarding. Before my children, my focus before and during performances would hinge entirely around the concert, but today, now with my children, I am somewhere in the back of mind, thinking, “I hope they had a good day at school, I hope they have eaten well, I hope they are sleeping well”. The usual worries all parents have!

Which performances/recordings are you most proud of?

Always wanting to improve on the last performance/recording is a common trait in performers and I share this!

Of course there have been certain performances that have been more satisfying than others, not only in terms of my particular performance, but also when the audience is so reactive and appreciative, it is a very special moment. I really appreciate also when sometimes members of the public write to me following a performance to let me know how much they enjoyed that particular concert or how much they enjoyed the last album.

Which particular works do you think you perform best?

In giving an interpretation to any one work, I really try to show what might be new to discover in the piece. In this sense, I think I convey Beethoven quite well. The French composers also seem to suit me; maybe it’s being married to someone French!

How do you make your repertoire choices from season to season?

What’s great about mixing chamber, duo and solo repertoire in a season is that there is an abundance of choice! It’s common these days to link a theme to a programme so that gives me a certain guideline. Otherwise for concerto dates, it’s quite often what the promoter has in mind for the season alongside the choice from the conductor so I need to be quite flexible for these dates.

Do you have a favourite concert venue to perform in and why?

Of the more well known venues, like many other performers, I would have to say the Wigmore Hall. Its reputation precedes it and the hall doesn’t disappoint. That said, there is a venue in France called Prieuré Sainte-Marie du Vilar that has to be included. It is a restored Romanian Orthodox Church, lost in the middle of the Pyrénées Orientales, and each year the monks and nuns organise a music festival for the community. The rawness of the venue and being surrounded by the stones impregnated with history gives a very unique atmosphere.

What is your most memorable concert experience?

I gave a series of concerts in Greece and one of the venues was in Patras. What was most striking about the make-up of this audience was that it was treated as a family outing. The children were all placed in the front rows, some not abiding by the ‘silence code’ of a concert, but it didn’t matter. At the end of each work, they applauded enthusiastically and seemed to enjoy the concert as much as the adults. It reminded me of my first impressions of attending performances and I hope I was able to communicate something to them with the Mozart concerto that I performed at the time.

As a musician, what is your definition of success?

When you feel you have found your voice and you have the opportunities to express this.

What do you consider to be the most important ideas and concepts to impart to aspiring musicians?

Never be afraid to be wrong and learn from everyone. Watch and watch and listen and listen again. There is so much archive available on the internet today. It’s important, I think, to be open to all interpretations and techniques of playing before creating and defining your own.

What is your idea of perfect happiness?

Two answers to this question. It would be either to find the time between concerts and practice for a good dance session with my husband and children because we always end up by collapsing in laughter. Otherwise it would be to take time out from playing to be by the sea with the family and catch up reading and a good glass of wine to hand.

Min-Jung Kym’s debut recording of Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 4 and Mendelssohn’s Double Concerto is available now. Further information

Min-Jung Kym is establishing herself as an artist bringing fresh quality and musicianship to her performances. Since her London solo concert debut at the age of just 12, she has performed at the Barbican Centre, Wigmore Hall, Cadogan Hall, Royal Festival Hall, Queen Elizabeth Hall, UNESCO in Paris, the National Museum of Korea in Seoul, South Korea and many, many other venues.

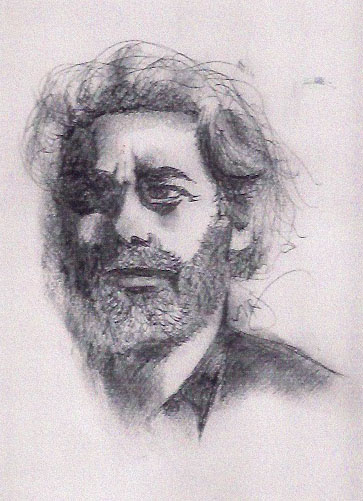

(artist photo: Arno MiseEnavant)

Guest interview by Michael Johnson

Guest interview by Michael Johnson