Guest post by Clare Stevens

Have you ever heard a cembal d’amour? Have you even heard of it? I certainly hadn’t before attending this year’s Early Music Festival in Haapsalu, Estonia. One of the weekend’s concerts was a duo recital by keyboard players Taavi Kerikmäe and Anna-Liisa Eller. While Eller switched from the psaltery to its larger sibling the arpanetta – double-sided and chromatic, like a harpsichord standing vertically upright – to the Estonian kannel – a chromatic zither – and folk kannel, Kerikmäe played the cembal d’amour, a brand new instrument completed earlier this year by Latvian harpsichord maker Kaspars Putrinš.

As far as is possible it is a reproduction of a keyboard instrument invented by Gottfried Silbermann (1683–1753) of Freiburg. Silbermann’s work as an organ builder was highly regarded by J S Bach, and he was also well known for his clavichords, one of which was prized by C P E Bach. He created the cembal d’amour in 1721, to a commission from the Estonian composer, performer and poet Regina Gertrud König (née Schwartz), wife of Dresden’s court poet Ulrich König. It was a clavichord with strings of approximately twice the normal length, which were struck by their tangents at precisely their midpoint – it seems that what König was after was a louder sound than the traditionally very quiet clavichord.

(photos by SabineBurger)

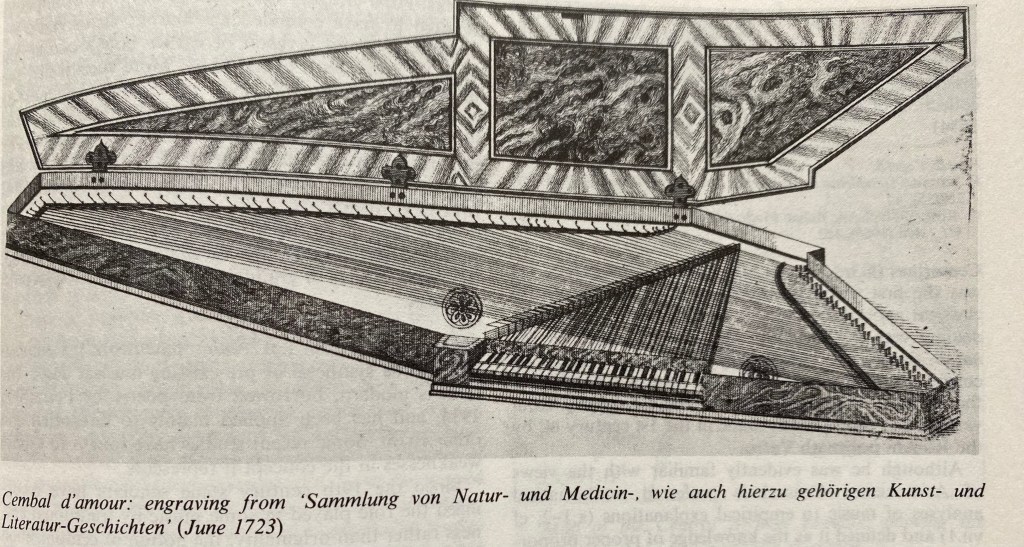

Silbermann’s original instrument has not survived, but its invention was announced in the Leipzig-produced Sammlung von Natur-und Medicin-, wie auch Hierzu gehörigen Kunst-und Literatur- Geschisten (Catalogue of natural and medical, as well as related art and literary histories) for July 1721. It was pictured in the June 1723 edition of the same publication and in a coloured drawing among the papers of the composer and musicologist Johann Matheson, a contemporary of Silbermann. Another description and diagram can be found in J F Agricola’s annotations to Jacob Adlung’s Musica mechanica organoedi (1768).

Taavi Kerikmäe is best known as a composer and performer of contemporary and experimental music, both film scores and art music; he is Head of the Estonian Contemporary Music Centre, and has collaborated with composers such as Pierre Boulez, Kaaija Saariaho, Tristan Murail and Louis Andriessen. But he has recently been exploring early music, especially clavichords, in performance with his duo partner Anna-Liisa Eller (who is also his wife).

Their Haapsalu recital consisted entirely of music by David Kellner (?1670 –1748), a composer, organist, poet and musicologist who was also the stepfather of Regina Gertrud König, commissioner of the first cembal d’amour. Born in Germany, Kellner studied at Estonia’s University of Tartu from 1694 and married König’s mother Dorothea Schwartz, daughter of the city’s mayor. He is known to have applied for the position of organist in the Swedish church in Tartu, later worked for a short time as organist of St Nicholas Church in Tallinn, and in 1732 published a treatise on continuo-playing which was printed in Swedish, German, Dutch and Russian, and survives in numerous reprints. Unfortunately the only music by Kellner to have survived is a collection of sixteen lute pieces in tablature, published

in 1747. Eller and Kerikmäe have arranged these for the assortment of instruments that we heard in Haapsalu, adding a basso continuo to bring out the beauty of Kellner’s music, which they feel is a hidden treasure of Estonian baroque music, and deserves an audience beyond lute and guitar players. Taking place in the gorgeous sixteenth-century Lutheran Church of St John, the concert was one of the quietest I’ve ever attended – despite the cembalo d-amour’s additional power compared to a normal clavichord – but the beauty of the different instrumental timbres repaid the intensity of the listening experience as these skilled musicians presented a sequence of elegant dance movements, taken mainly from Kellner’s Fantasias in different keys.

The day after the showcase concert Kerikmäe and Kaspars Putrinš set up the cembal d’amour in the salon of the Lahe Guest House for an afternoon lecture-demonstration that allowed audience members to experience the sound in a more intimate acoustic and find out more about the reconstruction project. Kerikmäe began by explaining for the non-specialists among us the crucial difference between a harpsichord, which has plucked strings, and a clavichord, where they are hit, and how this means that the harpsichord is louder, but the clavichord allows for more dynamic variation according to the pressure exerted by the player, so it is more subtle.

Silbermann’s concept for the cembal d’amore was not just to do with its extra long strings, but the fact that they vibrated independently from two bridges, one in the normal position to the right of the keyboard, and one behind and to the left of the keyboard, resonating from two soundboards on two sides of the irregularly-shaped instrument. We don’t know whether König wanted it to accompany herself singing or to use as part of a chamber ensemble, but the name is believed to derive from its suitability for performances alongside the viola d’amore.

Other contemporary makers did try to copy Silbermann’s idea, but he was very protective of his concept and sued them. Only one antique instrument survives, in a Helsinki museum, but it is much damaged. There were several twentieth-century versions, but most are now lost and they do not seem to have been designed to the same proportions as Silbermann’s. Putrinš explained that his new instrument is not a copy but a prototype, based primarily on the Matheson drawings. Building it was a challenge, but has provided a starting point for further exploration.

Kerikmäe and Eller are also keen to draw attention to the legacy of Regina Gertrud König, who was highly respected in her lifetime and can probably be considered as Estonia’s first female composer, but they are hampered by the fact that none of her music has yet been discovered. For now her influence is primarily represented by the instrument that she commissioned and its latest incarnation.

More information about the music of David Kellner and about the Kerikmäe Eller Duo: www.davidkellner.eu

(Photos by Clare Stevens)

Clare Stevens is a freelance writer, editor and publicist, specialising in classical music, choral music and music education. After 30 years living and working in London, she is now based in the Welsh Marches.

This site is free to access and ad-free, and takes many hours to research and maintain. Why not support The Cross-Eyed pianist here:

Discover more from The Cross-Eyed Pianist

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.